Where are the Women in the Curriculum? PGCE Historians, mentors and tutors reflect on a pressing question

PGCE History Subject Leader Tom Donnai ponders some of the issues facing teacher educators

I recently asked my 9 year-old daughter a fairly simple question, as she walked through the front door after her first day back at school. ‘What is History?’ Her reply, though fairly standard in some senses, was a little depressing: ‘Erm…..like, Kings. Battles? Important stuff that happened a long time ago. And bad men who started wars too.’ A fairly simplistic reading of the past, we would all agree, but the reference to ‘great and bad men’ from the past is troubling, and in many ways illustrates the narrowness of both school curricula and the way History is taught in schools. Where were the women in her response, in her reading of the past? Why is school History still dominated by ‘pale, male and stale’ narratives that marginalise women’s stories?

As teacher educators, there is much we can do to tackle the pressing issue of representative curriculum building. As is so often the case, when dealing with marginalised or under-represented groups, the key to success is helping trainees to build awareness and grow their subject knowledge. This approach has borne fruit in recent years with our work on LGBT+ History, and the key for me has been locating subject specific, practitioner expertise from teachers and schools who are getting it right. Locating expertise within the University of Manchester has also been important, with historians such as Dr Janette Martin and Dr Eloise Moss providing unique insights into, amongst other things, the role of women at Peterloo and the use of oral testimonies in planning ‘representative’ enquiries. A great PGCE course needs to balance theoretical and practical expertise and we’re lucky to have both at our disposal here at UoM.

I first became aware of the excellent work Loreto Grammar School do in this area through a good friend whose daughters both attend, and made contact with Jen Turner, (the Head of History) last year. It quickly became apparent to me that this was the ‘pocket of outstanding practice’ that I’d been looking for, and Jen and I quickly began sketching out a unit on women in the curriculum to be delivered this year, as well as a research project that is currently running parallel to the taught sessions. The aim of the collaboration is twofold: to increase the knowledge and skills of PGCE Historians in this area, and to empower them to build their own lessons and curricula, which will put women at the centre of the enquiry, and not on the sidelines. Early signs are most encouraging, and PGCE Historians are in the process of creating their own lessons that will be showcased in June at our annual ‘representative Curriculum showcase event at UoM. Colleagues and mentors from partner schools are cordially invited to attend and learn more about our work!

Prime candidates for a historical enquiry…but can you name them both?

Practitioner perspectives by Jen Turner, Head of History, Loreto Grammar School:

I am delighted to have the opportunity to shape a new generation of teachers’ perspectives on women’s history. It is evident that there is still plenty of work to do in creating the integrated curricula that many practitioners have been calling for on the pages of Teaching History and elsewhere for… well… a depressingly long time! Susanna Boyd argues eloquently for a curriculum which integrates the experience of women, echoing earlier calls by Joanne Pearson and Lockyer and Tazzymant in Teaching History magazine. Claire Holliss’ and Paula Worth’s blog posts have taken the discussion onwards – but still, women’s history continues to be underrepresented in schools.

There are evidently still obstacles to clear, but clearing them has never felt more important. I passionately believe in the importance of representative history for its own sake, as simply good history- how can we claim to be doing history fully if we largely ignore the experiences of over half the population? But in 2021, it’s impossible not to also feel the pressure to really get this right in a pastoral sense, for the sake of the young women and men in our care. The presence of peer on peer abuse in schools is escalating. The issue of violence against women is dominating the media. The heightened awareness of the damage that social media can do our young people, and especially teenage girls, is pressing on our thoughts. In this situation, how can we deliver a curriculum that reinforces gender stereotypes? That ignores women and silences their voices?

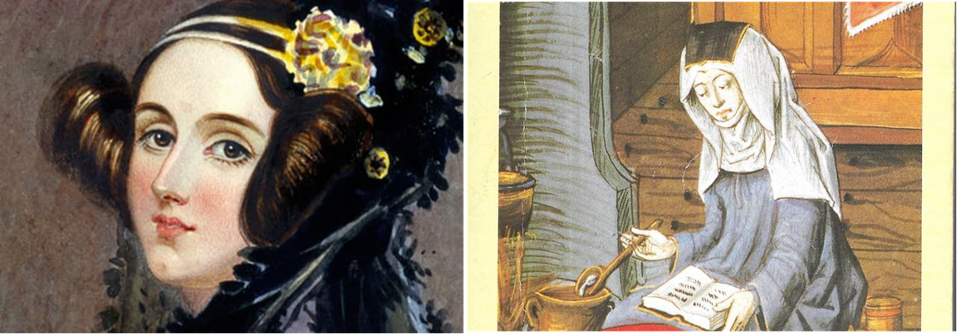

In 2020-1, I delivered a session for that year’s PGCE cohort who were then part way through their placement. Their experiences were really enlightening- across Greater Manchester, there are schools doing amazing work, but clearly areas where women’s history is still seen as a ‘bolt-on’- if indeed it is present at all. So the chance to work more closely with the PGCE History cohort this year was a golden opportunity. My first session aimed to try to dismantle the ‘bolt on’ approach and equip trainee teachers with the tools and confidence to plan and teach exciting, representative history. We studied some of the obstacles and I was delighted with how quickly the trainee teachers were able to understand some of the challenges facing schools, including those from wider society (try doing a Google image search of any traditional KS3 history topic and see how many female faces you see!) and from other pressures like exam board specifications. The student teachers were really engaged and many were clearly bringing a strong sense of social justice to their idea of what good teaching might look like.

Jen Turner helps PGCE Historians deconstruct a typical KS3 History curriculum…and rebuild a more representative, inclusive version

A curriculum is usually a ‘work in progress’, especially in history where we have a responsibility to stay up to date with changing historiography and new research. I shared some of the journey that my department is undertaking in weaving women’s stories into our updated Year 7 curriculum, including making use of the Paston letters and the experience of women involved in the crusading movement. Subject knowledge is so crucial and teachers are busy people- but most of us also love history and so I shared some tips for quick and easy ways to keep updating your subject knowledge even when the marking is piling up!

It was such a pleasure to lead a session with this group of beginning teachers and I can’t wait to see how they take the theory into practice as they start their placements.

PGCE Historians Monika Zdunek and Isobel Redmond summarises her experience

Week two began with a bang as we traversed deeper into the world of curriculum building. Our guide was the fantastic guest speaker, Jen Turner, Head of History at Loreto Grammar and passionate advocate of building a better and more representative History curriculum. As we’ve seen already this year, many of the problems with building representative curricula [in all subjects] centre around teacher expertise and subject knowledge: in essence, you can’t build the house if you don’t have the bricks! In enlisting expert ‘teacher expertise’, Tom, the subject leader for PGCE History, has sought to help us build first subject knowledge, and thereafter the ability to start planning our own representative History curricula.

Jen demonstrated to us the various ways in which women could be included in the curriculum. The label ‘Women’s History’ is problematic in many ways [surely it’s just good History], and Jen highlighted the dangers of simply ‘slotting’ in a succession of narratives about ‘great women’ into the standard KS3 curriculum. Such an approach is tokenistic at best, and leads to departments wrongly assuming that ‘women’s history’ has been ‘covered’. Integration, therefore, was the word of the day, and Jen presented us with a number of case studies that proved to be really helpful in focusing our thinking.

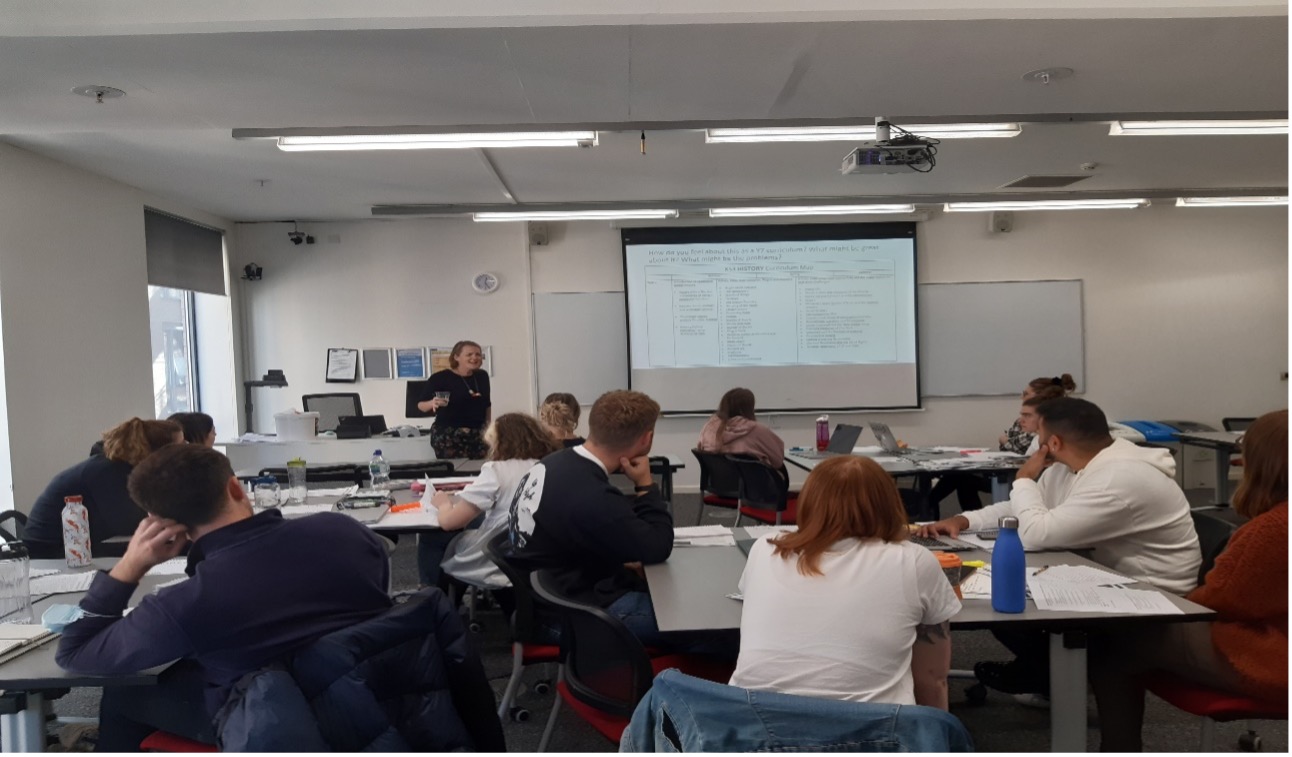

PGCE Historians Anna, Jack, Ellie and Monika hard at work planning lessons with women at the forefront of the enquiry

Harriet Tubman, liberator of enslaved peoples, Annie Besant, iconic match-girl, and the political powerhouses that were English Civil War petitioners, were viewed as prime examples for women who could be included alongside the typical ‘pale, male and stale’ history which overwhelms the curriculum. As an expert in medieval History I was thrilled to see Margery Kempe suggested as another case study; this mystic is credited with publishing the first autobiography in the English language! The importance of including these stories in our curricula are twofold: firstly, such lessons are vital for young girls to learn as they develop their own sense of self-worth and resilience in the real world, helping to challenge sexism and reposition women in historical narratives. Such lessons are equally vital for young boys, helping them to understand the fact that the ‘dominant historical narrative’ is not always the most accurate reading of the past. What a better platform on which to level the playing field between genders than the history of where they themselves came from?

As the day progressed, Jen equipped us with the tools to truly make a difference in moulding the curriculum into a more diverse, representational and equal learning experience. Take for example, the Crusades. Jen took us on her journey to include women in what is generally considered to be a period in history dominated by male narratives. Jen outlined her series of lessons on the Crusades and illustrated that both men and women, of both upper and lower classes, went on crusades; as is so often the case with marginalised histories, the trick is locating accounts and testimonies and ‘finding’ the women. We were then given the opportunity to attempt this ourselves, creating lesson plans with robust , vibrant enquiry questions…with women at the centre of the enquiry. Ranging from people on the home front, to constraints to plantation life, and whether the Big Three were the only players of Versailles, we found countless topics in which there was no need for to ‘shoehorn’ women in. The shoe fit exactly! Women are everywhere in History and should be represented as such. This, for me, was the key takeaway from this session: women’s history is all around us and doesn’t need to be signposted. As the next generation of educators, we just need to look harder.

By PGCE Historian Monika Zdunek

The writer, Virginia Wolf, articulates in A Room of One’s Own (1929) the place of women’s stories in the historical record, claiming, ‘Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, […], was often a woman.’ A century on, little appears to have changed in the History curriculum – a point argued during Monday’s session by Loreto Grammar School’s Head of History, Jen Turner.

A scepticism of the validity of ‘women’s history,’ as Jen Turner explained, often leads to women’s history being largely ignored in curricula and included only on a ‘tokenistic’ basis. In reflecting on her own curriculum, Jen argued for a ‘seamless’ blending of interesting historic females into the curriculum to captivate learners’ historical imagination.

This scattering of women throughout curricula, as demonstrated by Turner, appears the best solution to challenging the silencing of women’s voices. For instance, Turner recommends that when teaching the English Civil War, that the experiences of women such as Lucy Hay, Countess of Carlisle are included to illustrate that despite women’s position in society, some were able to wield substantial political influence.

Not only does the scattering of women throughout the History curriculum ensure that lessons inspire intellectual curiosity, it also ensures that young people are able to construct and reflect on their own identities through marginalised histories. As such, I am keen to deliver a diverse and inclusive curriculum which inspires the next generation of women.

By PGCE Historian Isobel Redmond

0 Comments